Long lauded as a choice favoured by architects but questioned by environmentalists, Associate Director David Brooks explains how the conversation about concrete is shifting.

It is widely known in Australia that the construction industry is a significant contributor to the national carbon footprint. Concrete, and its extensive use, equates to a sizable proportion of this carbon footprint due to its favoured qualities of speed, strength and fire rating. To discuss concrete’s environmental impact as a building material is to primarily discuss embodied energy.

Build less, with less

Most building materials require high-energy processes of raw material extraction. Additionally, most building materials require the destruction of natural environments for raw material extraction and contribute to landfill with waste products and offcuts. Simplistically speaking, to reduce the negative environmental impact we have to build less, with less. Concrete can contribute positively here through its durability, aesthetic endurance, waste minimization, versatility and increasingly, recyclability.

“Concrete has always been seen quite negatively, and, despite its popularity, this perception comes down to the fact that it hasn’t always been renewable – and like most building materials, a large portion has to be dug out of the ground as a raw material,” says David.

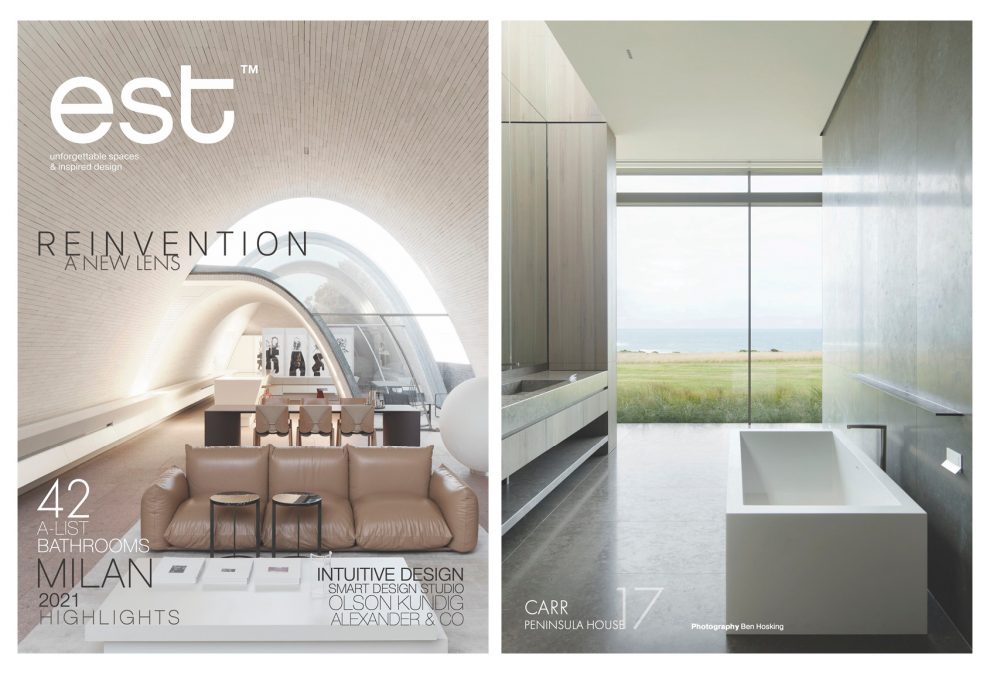

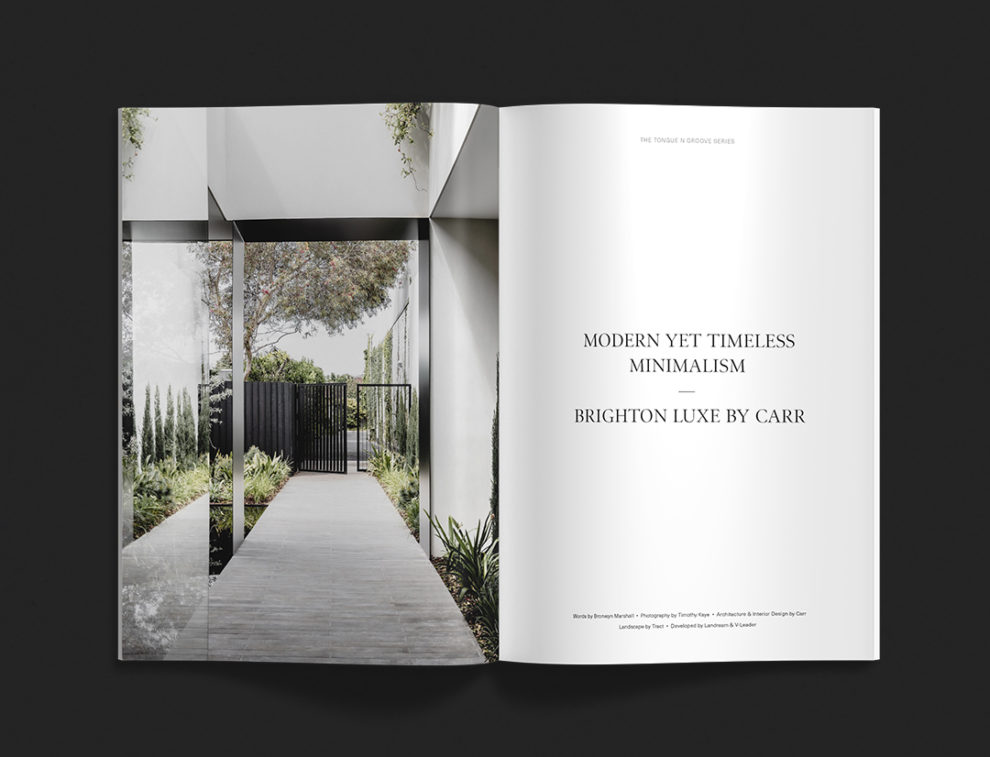

Dedicated to proposing enduring and timeless architectural responses, Carr has been an advocate for the robust and time-wearing material for many years for three primary reasons: longevity, authenticity and versatility.

Longevity

The building industry is not immune to the throw-away society. A building is torn down generally due to three factors: the loss of structural integrity, it’s stylistically no longer in vogue, or a building/structure that no longer meets the needs of contemporary functional requirements and standards.

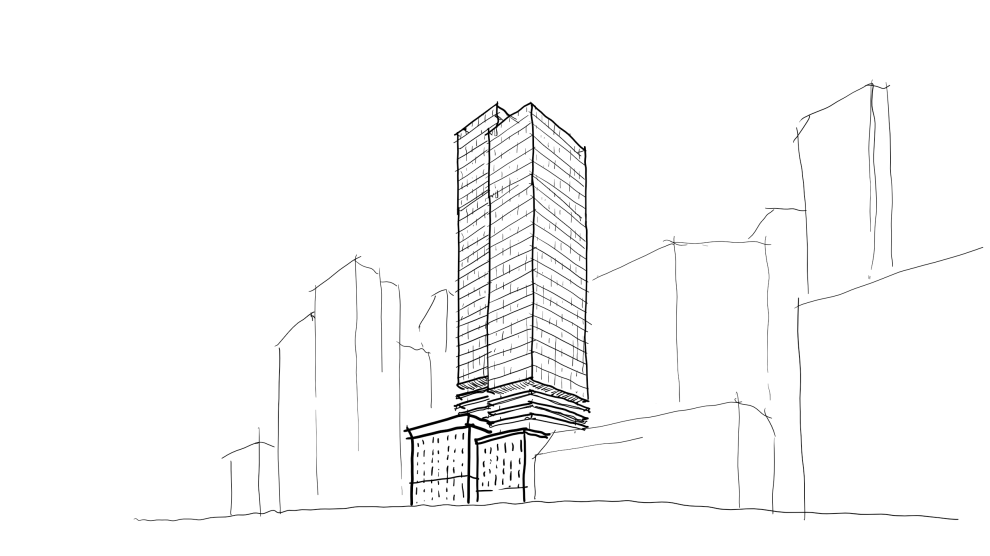

Concrete has the structural integrity and strength to last for large spans of time with fewer vertical supports for future flexibility. When architecture is produced with an enduring and timeless approach, coupled with a flexible structural layout, there is no reason why buildings cannot be built today to last centuries.

Authenticity

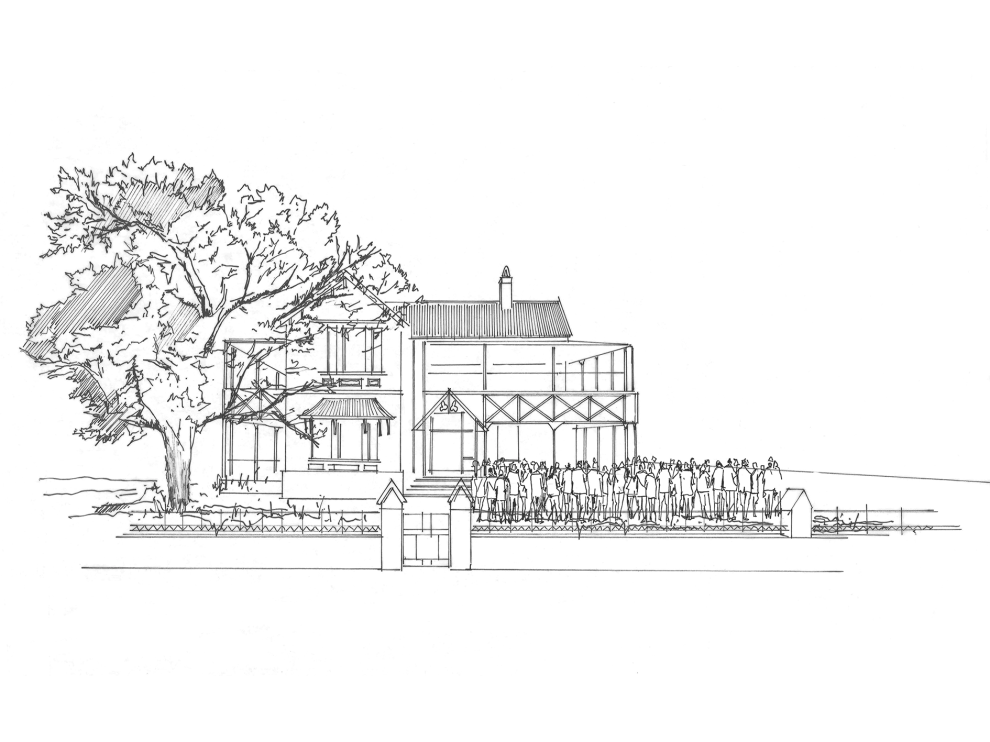

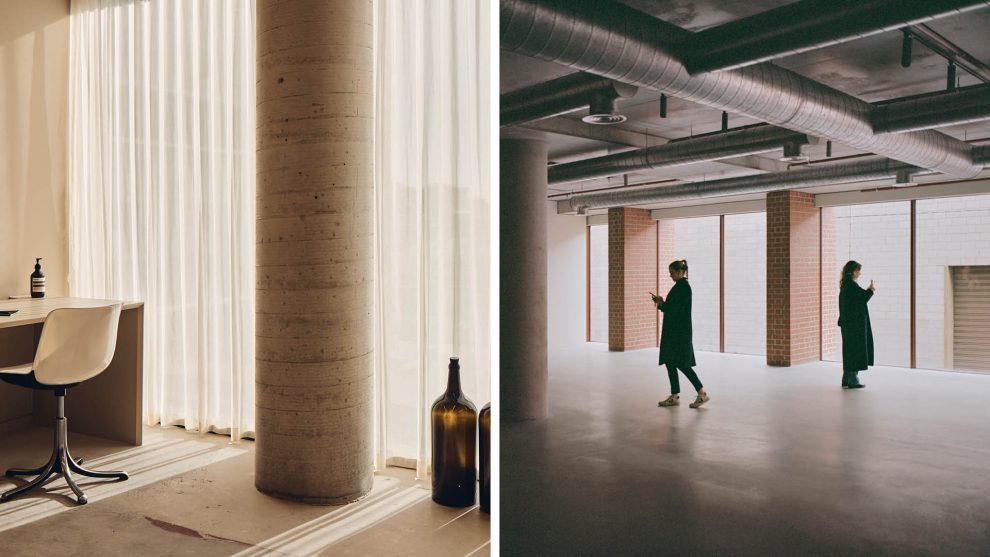

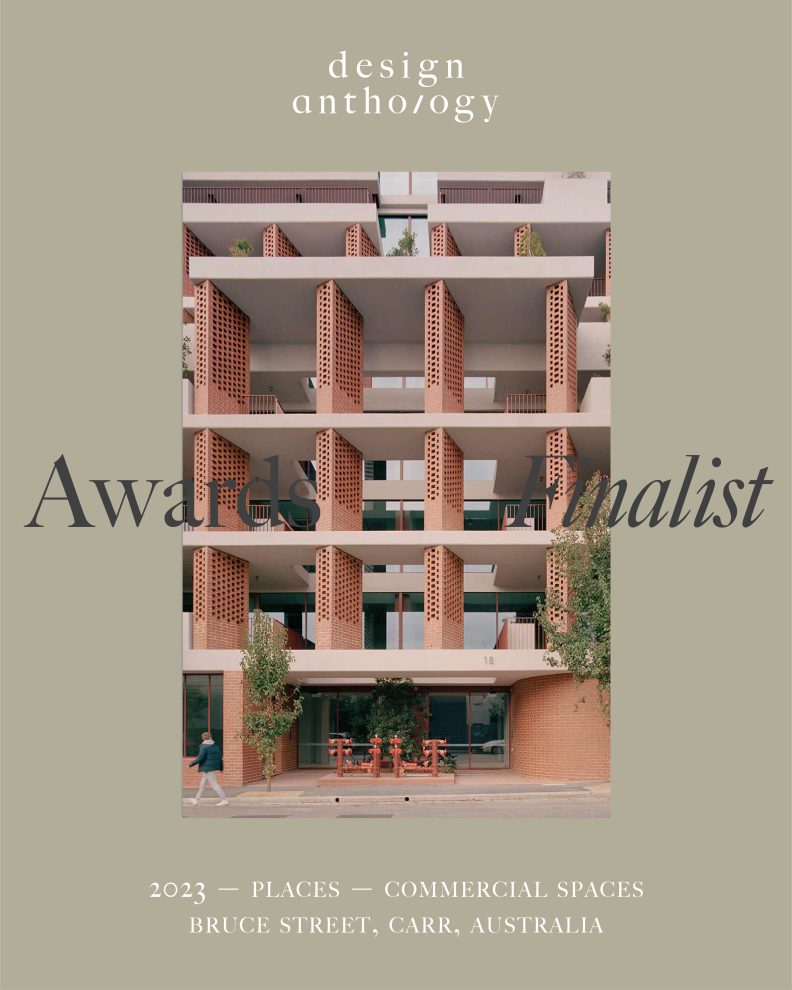

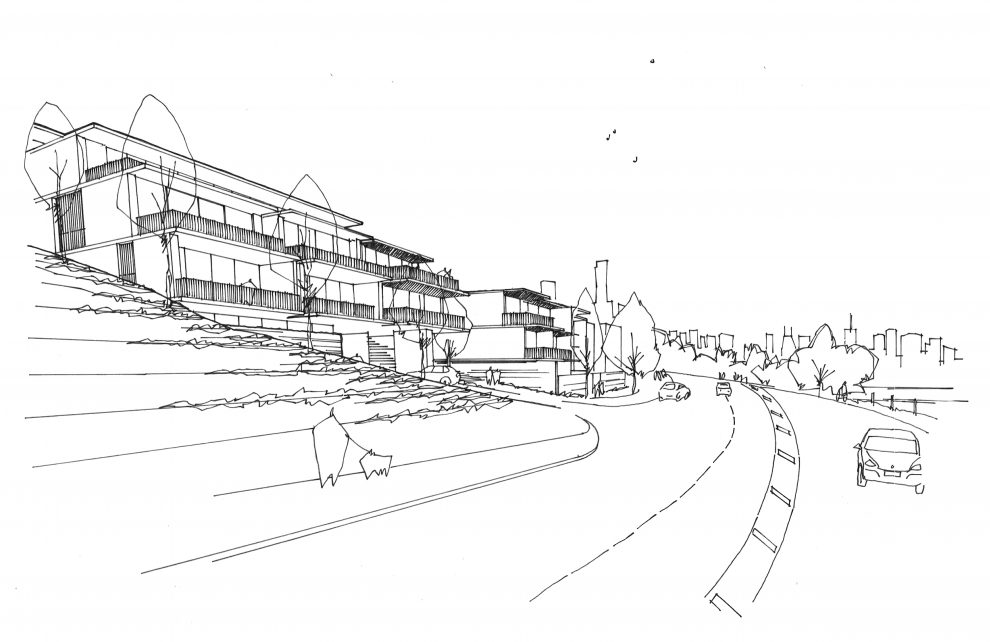

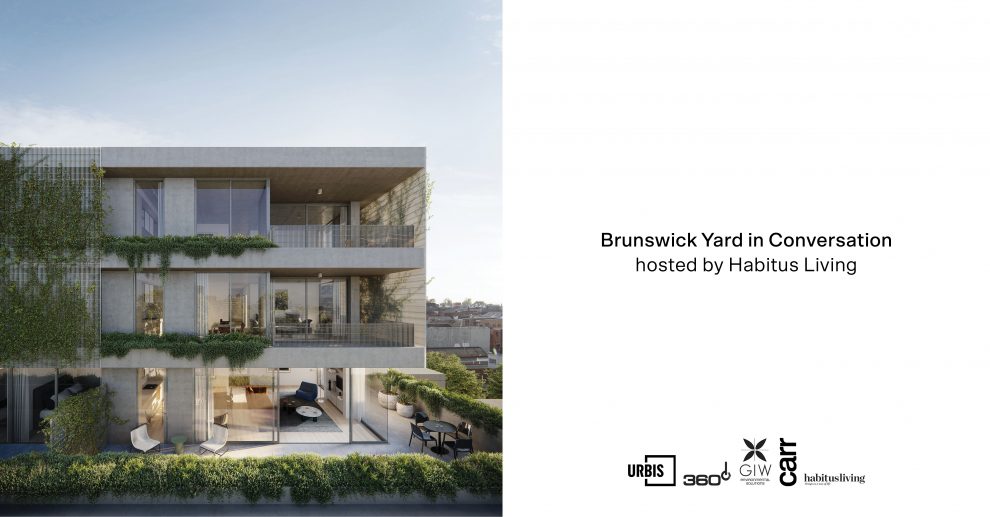

Two current projects by Carr: Como Terraces in South Yarra, and Brunswick Yard in Brunswick, fulfil quite differing briefs, yet have a clear commonality in responding to context. Both explore the raw honesty of concrete and the varied possibilities of finish through exploration of coloured oxides, aggregate mix and surface treatment.

“While concrete is structural, expressed and exposed, it has the ability to integrate multiple finishes that we’ve explored through a lot of experimentation with textures and tones, plus form and shape,” says David.

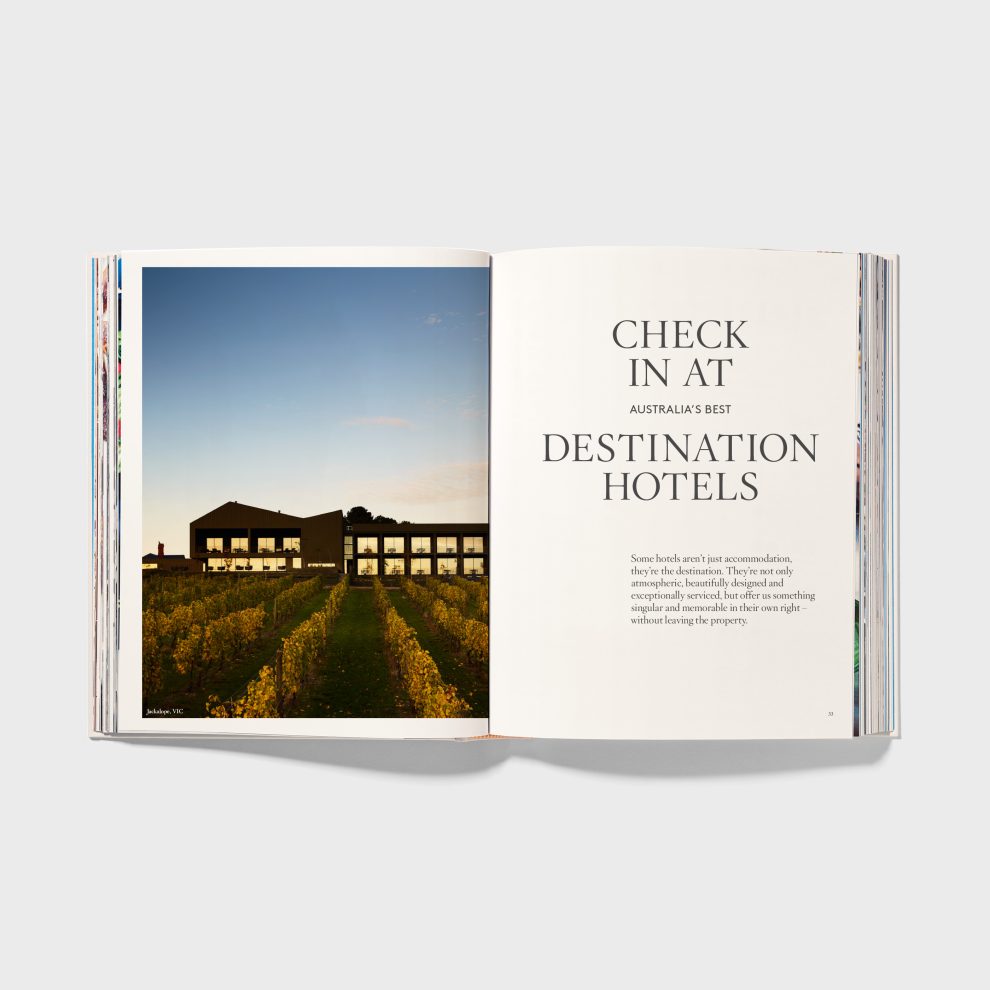

On a steep natural site sloping down towards the Yarra River, Como Terraces is a series of buildings clad in sandblasted concrete in tones sympathetic to this natural environment. By celebrating the diversity, precision and natural aging and wear of concrete, the material has become a signature of Carr’s work, as projects endure with an inherent grace. “There are a number of beautiful ways to use concrete,” adds David, “and when I think of the best examples that have patinaed over time, they grow in value particularly as patina becomes an indicator of time and permanence.”

Brunswick Yard, however, responds to the surrounding area and industrial history. Through the use of concrete, a raw and honest expression of the building shapes the building’s identity and creates a connection to place.

Versatility

Concrete’s versatility also contributes to embodied energy reduction, not only in construction but also in ongoing maintenance.

Concrete has the ability to be multiple things simultaneously: structure, façade cladding, fire rating, acoustic insulation, internal lining, internal finishes, internal lightweight structure. This is also a reduction in toxic adhesives and paints and so on, which require ongoing reapplication throughout the lifestyle of the building.

All of the alternative products that concrete can replace have embodied energy and wastage — through offcuts either on site or in the factory. Some of these offcuts can be recycled, but many cannot. While not wastage-free, concrete’s fluid nature allows it to be poured on site as required, minimising excess waste.

As an undercurrent to Carr’s philosophy, an ethos of longevity drives the resulting outcomes. Creating architecture that will continue in place, remain relevant and serve its purpose well beyond its current custodians is integral. So too is the integration of recycled parts and utilising improved practices to lessen the environmental effect.

However, due to its increased popularity afforded to its dexterity and economies of scale, more efficient practices are continually being developed.

“What is becoming more common, is that industry has been changing and evolving, allowing concrete to be recycled in so many new ways, and we are excited to be working with great innovators in this field,” explains David.

Increasingly also used as a replacement for gravel, recycled concrete is being seen more so in construction as a product that leaves the site and returns again in another use, instead of just being discarded entirely.

With the ability to be reused, to be agile, flexible overtime, offer thermal qualities, reduce waste and with an enduring strength, concrete bolsters the philosophy of building better and building less. To us, this is the true embodiment of what sustainable design aims to achieve.

Words by Bronwyn Marshall

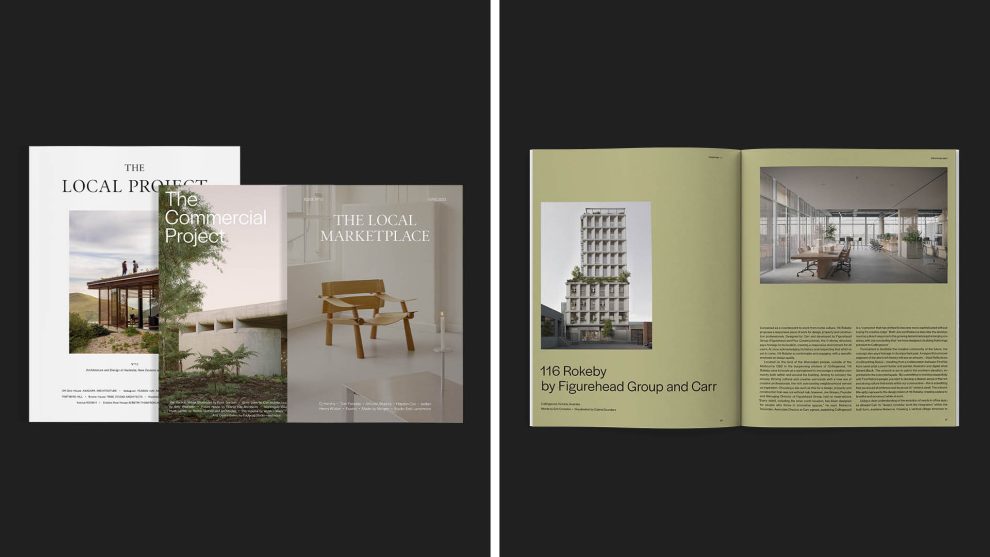

Read about the Rokeby Street Commercial Building and how it’s underpinned by environmental and wellness design consciousness, offering workplace with a rigorous approach to sustainability.