Having grown up surrounded by large-scale Victorian linen mills in Belfast – one of the most prominent cities impacted by the Industrial Revolution – Associate Director Stephen McGarry is fascinated by the craftsmanship, human scale tactility, and resilience of bricks.

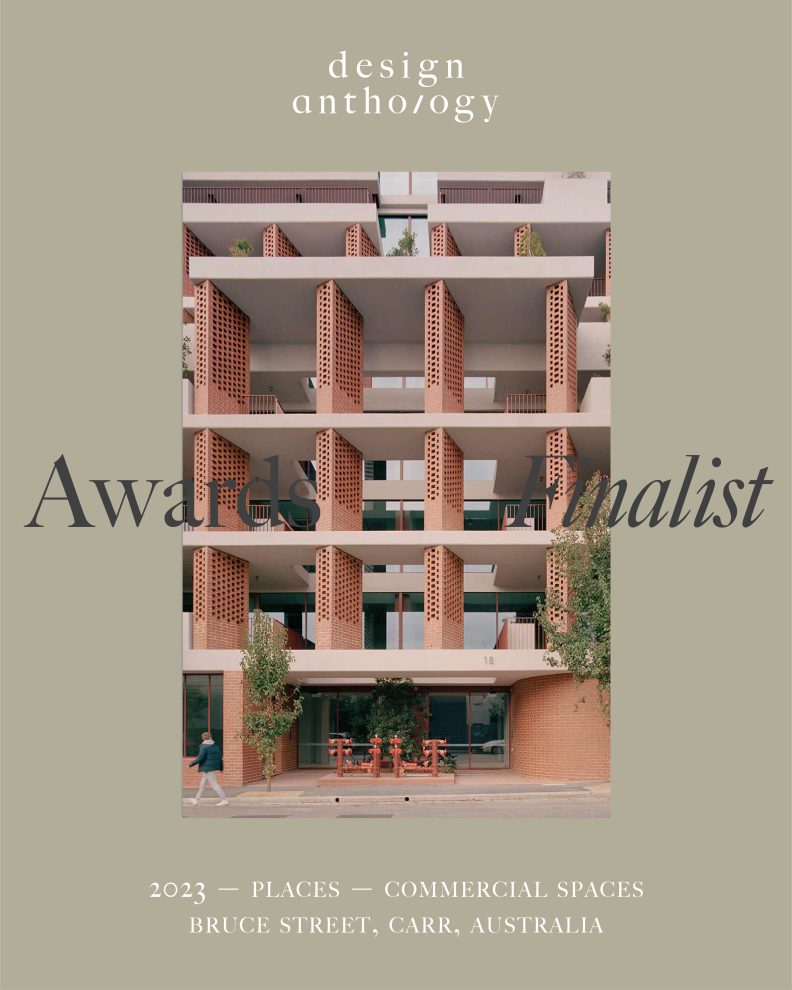

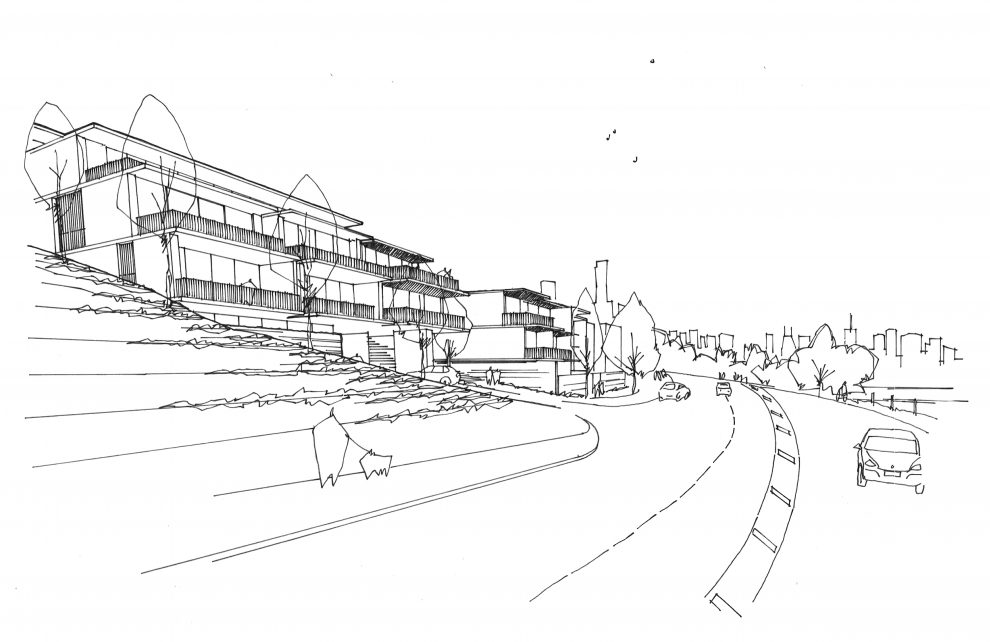

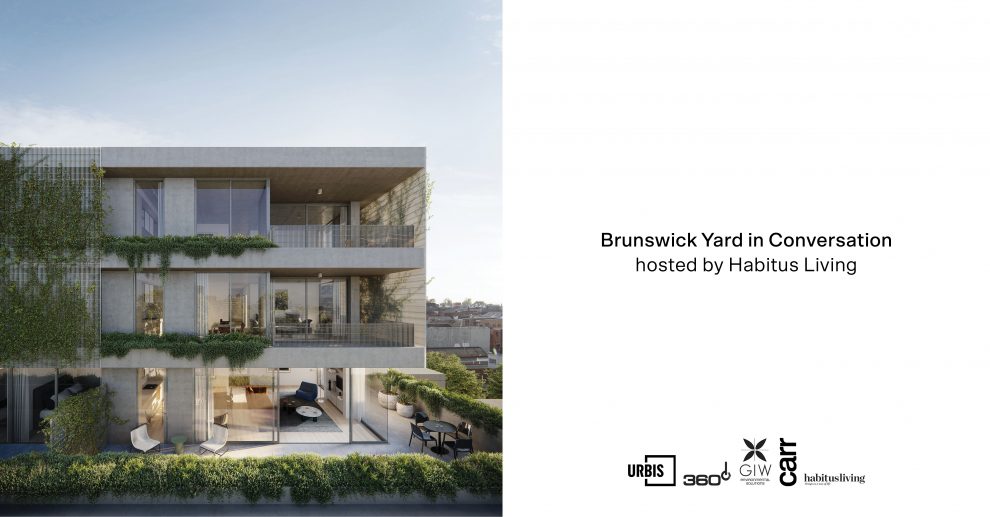

This passion can be seen in his design of Bruce Street, an eight-storey commercial development located within Kensington’s historic industrial precinct in Melbourne. Today, Stephen explains why brick remains an enduring, if at times overlooked, choice of building fabric.

“Brick is a material that’s etched into the fabric of Melbourne and its habitants,” says Stephen. “Similar to other heavy industrial cities and with the introduction of the pressed brick, Melbourne had beautiful examples of large-scale brick architecture that has been lost over the years.”

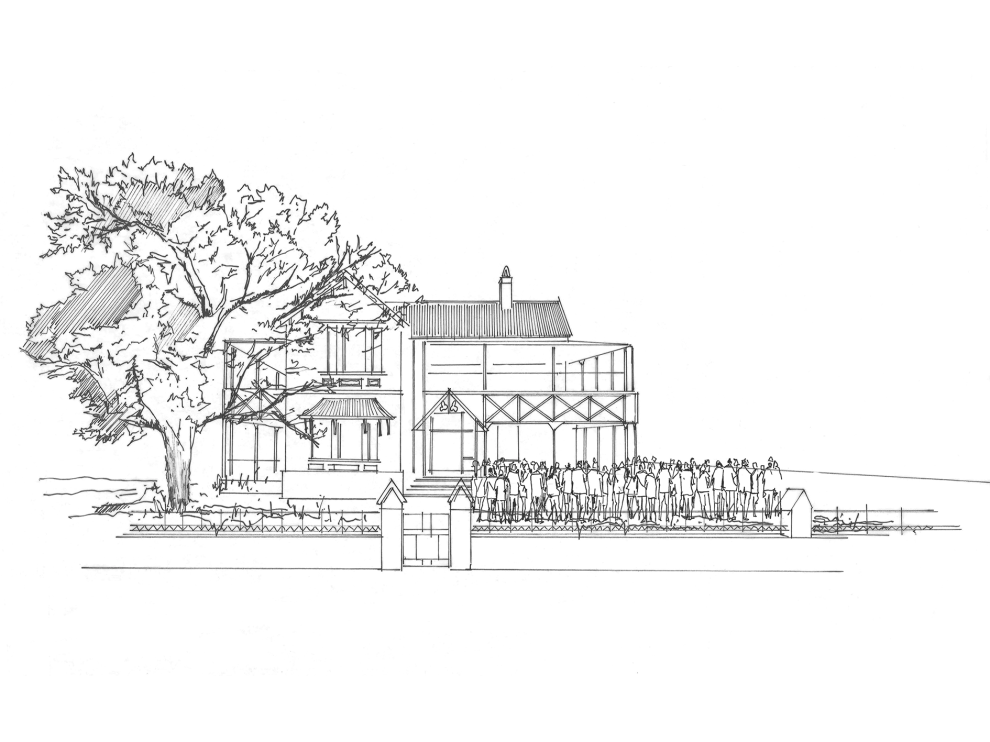

At the conception of any project, Stephen takes advantage of a project’s textural and historical context as a rich backdrop to positively add to. Bruce Street is a prime example of this. Defined by its streets of red brick warehouses, towering grain silos and the Younghusband Woolstore dating back to 1901, the new building is the first development of scale in the precinct. The design pays homage to the project’s historical site with expressed concrete slabs divided by red brick piers, complemented with fine metal balustrades.

Multi-faceted material

Along with its obvious aesthetic qualities, particularly within industrial areas, brick includes a range of environmental and commercial benefits. Brick possesses thermal mass qualities to reduce heating costs during winter and is cooling in summer. Highly resilient to water or sun exposure, brick is fireproof and an ideal noise-cancelling solution.

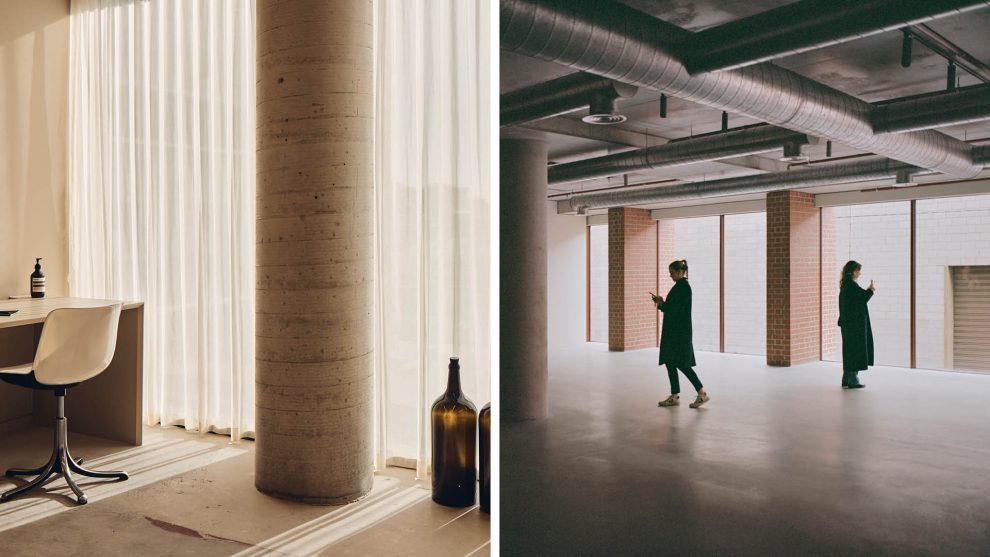

“In Bruce Street, we used brick on the west façade to create large blade walls to help shade against the western sun, framing views and creating external shaded social spaces for tenants,” explains Stephen. “And from a commercial perspective, bricks have a longevity and robustness to them. It’s a material that won’t date visually or functionally, rather add to the rich context and fabric of the area.”

Not only is brick easily recycled into new projects, such as in Bruce Street, but it derives from naturally occurring materials of shale and clay and does not emit volatile organic compounds.

Speaking the same material language

For Bruce Street, brick was an obvious choice as the predominant architectural material. “For me, if you didn’t use brick for that building considering it was the first development of scale in the area, then it would become somewhat alien rather than in conversation and unison with the context,” shares Stephen.

Along with the brick, the red ironmongery is another nod to the industrial past, through the use of metal screening, handrails, hinging and window framing. “Bruce Street is somewhat a modern reinterpretation of the warehouse context. The textural qualities of brick, the social connection of its use over hundreds of years, the craftsmanship of laying it and how the mortar is applied should be celebrated, and equal to other commonly used materials for this building typology. Brick is self-consciously the fabric of many cities and people’s psyches. This results in more engagement with the building due to this commonality and more humanistic tactility.”

At Carr, Stephen sees the role of architects and designers, to not only make beautiful buildings but also to enhance engagement with the built form and the environment in which they sit. “It is our job to positively add to society and those that use the space in and around, not just within.”

When context calls

Although Stephen is an advocate for the use of brick for structural and aesthetic purposes, he is quick to note that it should only be used if appropriate to the landscape. “Projects that showcase an extensive number of bricks will only be if the context calls for it. But understandably a particular brief, client vision of context may not justify its use. However, when brick is the predominant material within the environment and is ingrained in the social and architectural fabric of Melbourne, I see its use more warranted than not.”

Read why it pays for landlords to revitalise their commercial assets through unexpected and diverse interior design insertions.