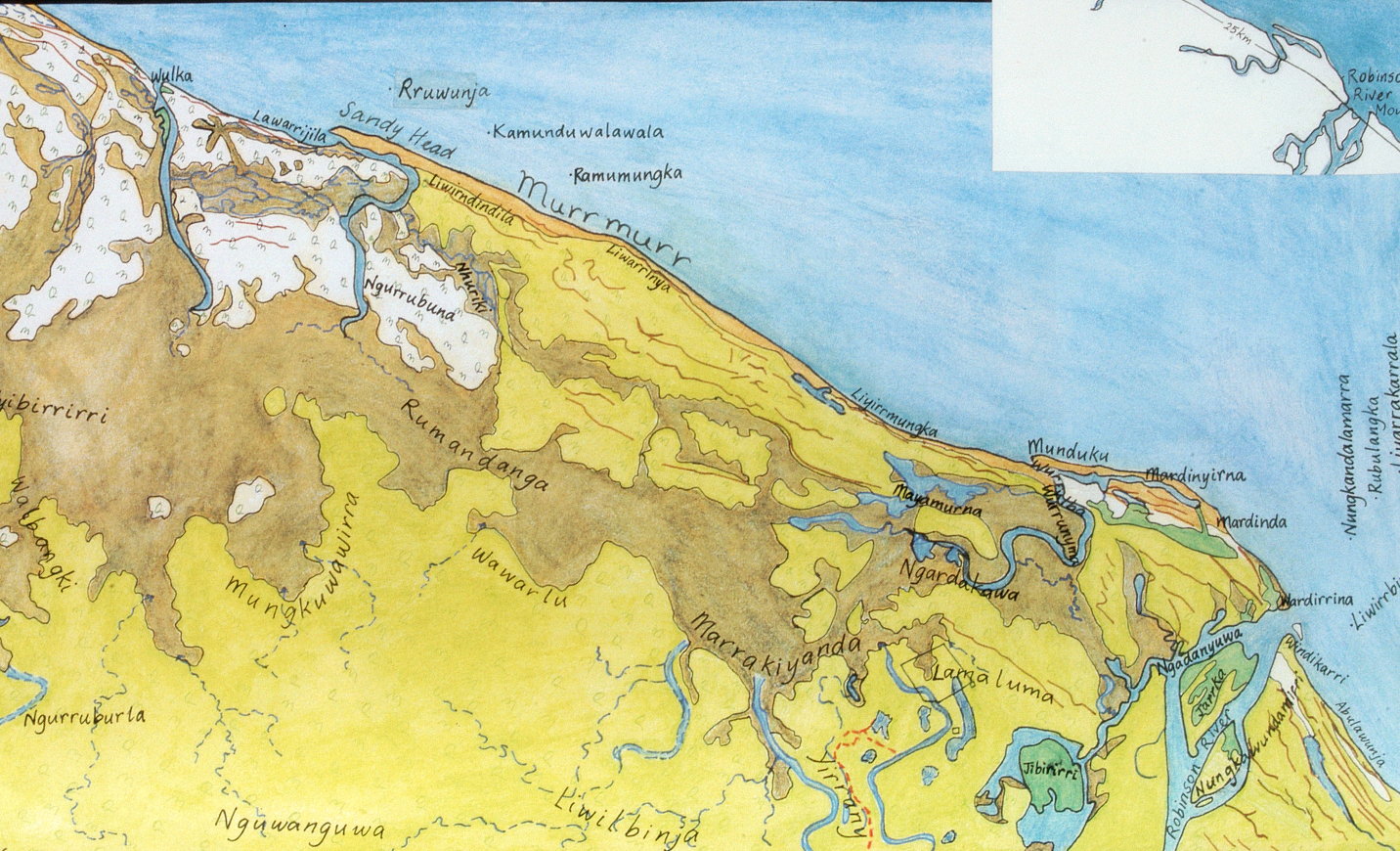

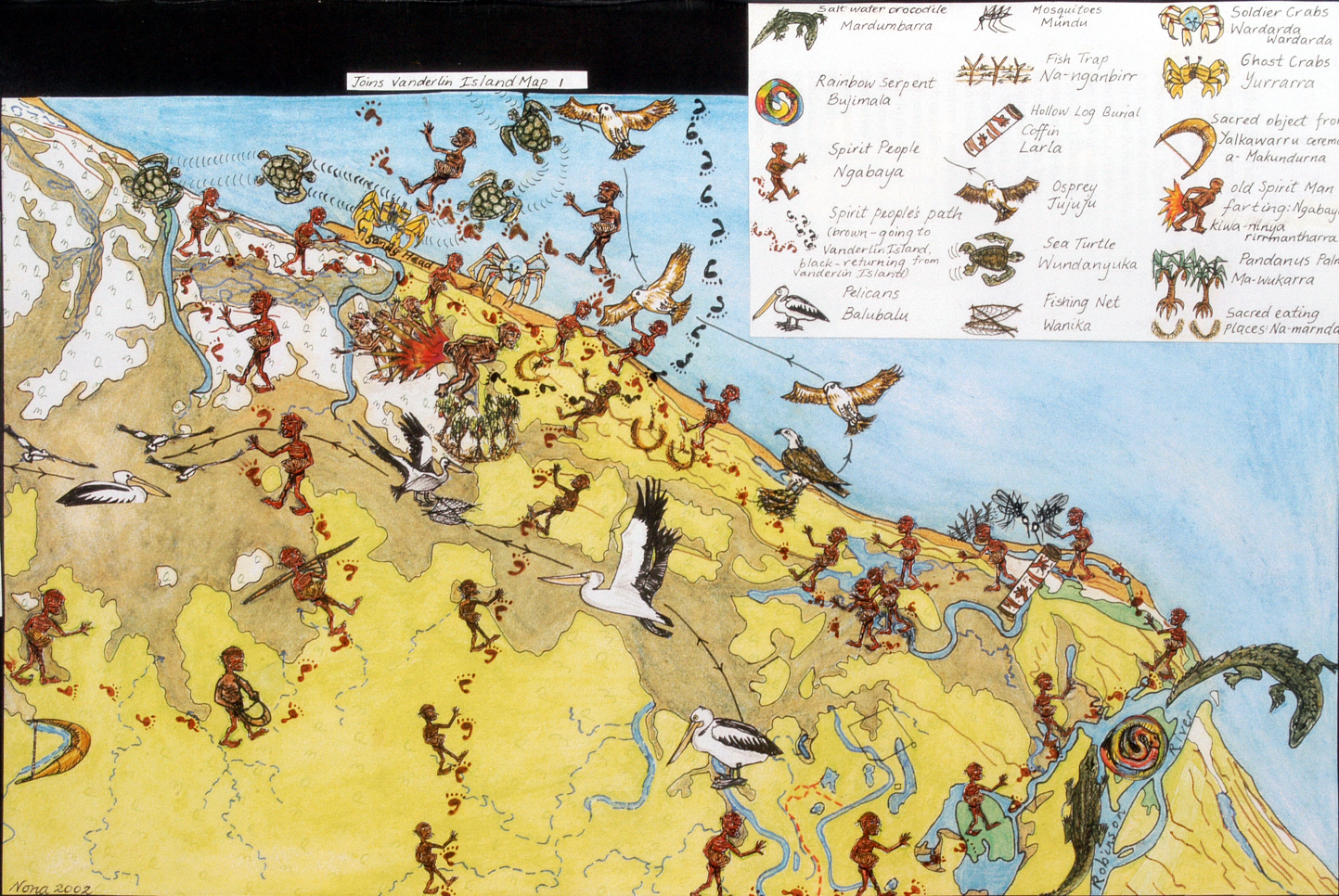

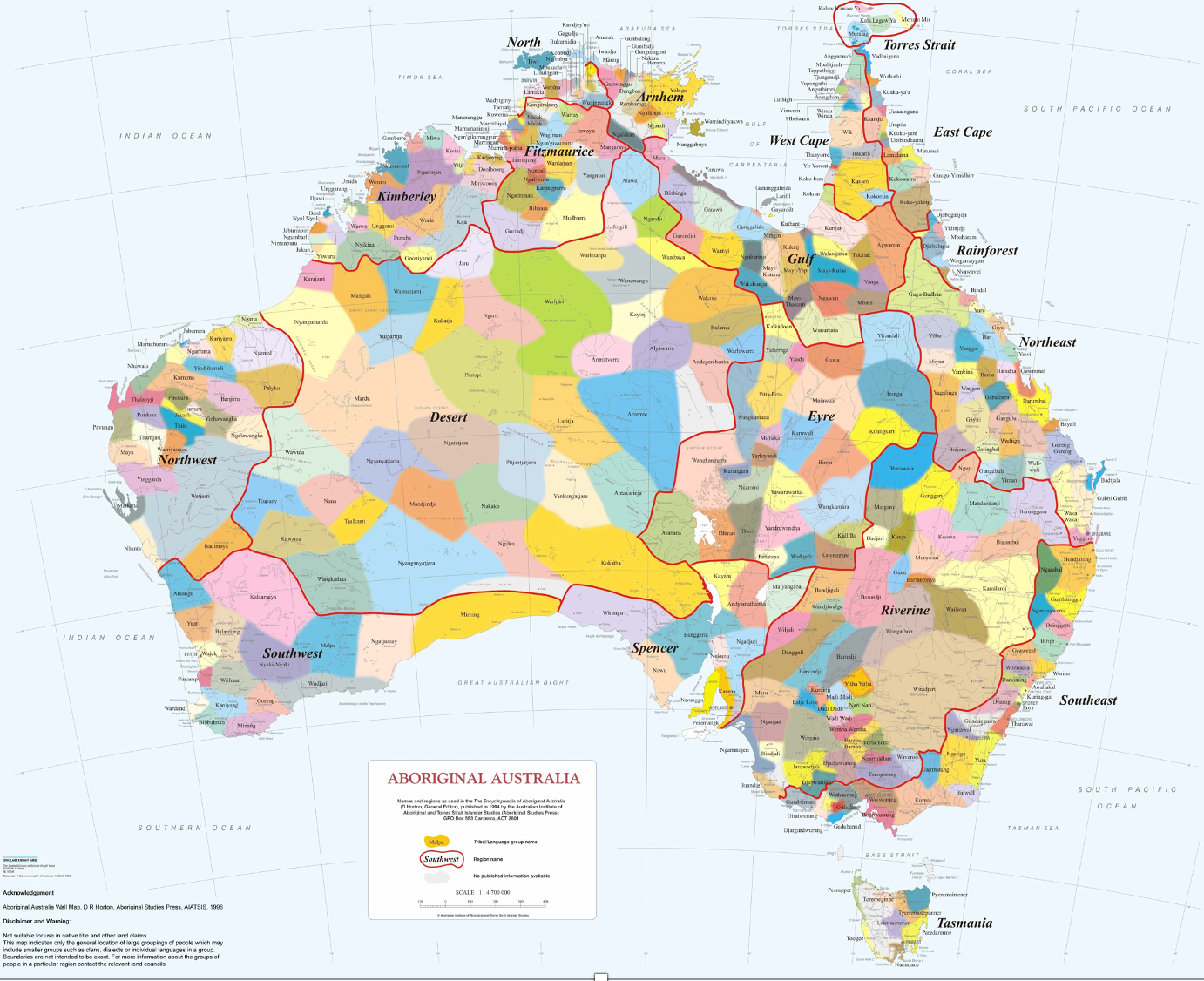

Living in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Northern Territory, for over 40 years, John Bradley has been steadily working with many of the senior members of the community to record stories and maps about country.

As one of the few people that speak Yanyuwa, John talks to us about his knowledge and experience living in Borroloola. During this time, John has been collecting and documenting wisdom and language of the Yanyuwa communities. This large body of work has surmounted into a project to preserve stories for future generations, which will be supported by cultural centre we are working on together in Borroloola.

You’ve spent 42 years in Borroloola. Tell us about your first memories arriving here. How did you go about learning the language, Yanyuwa?

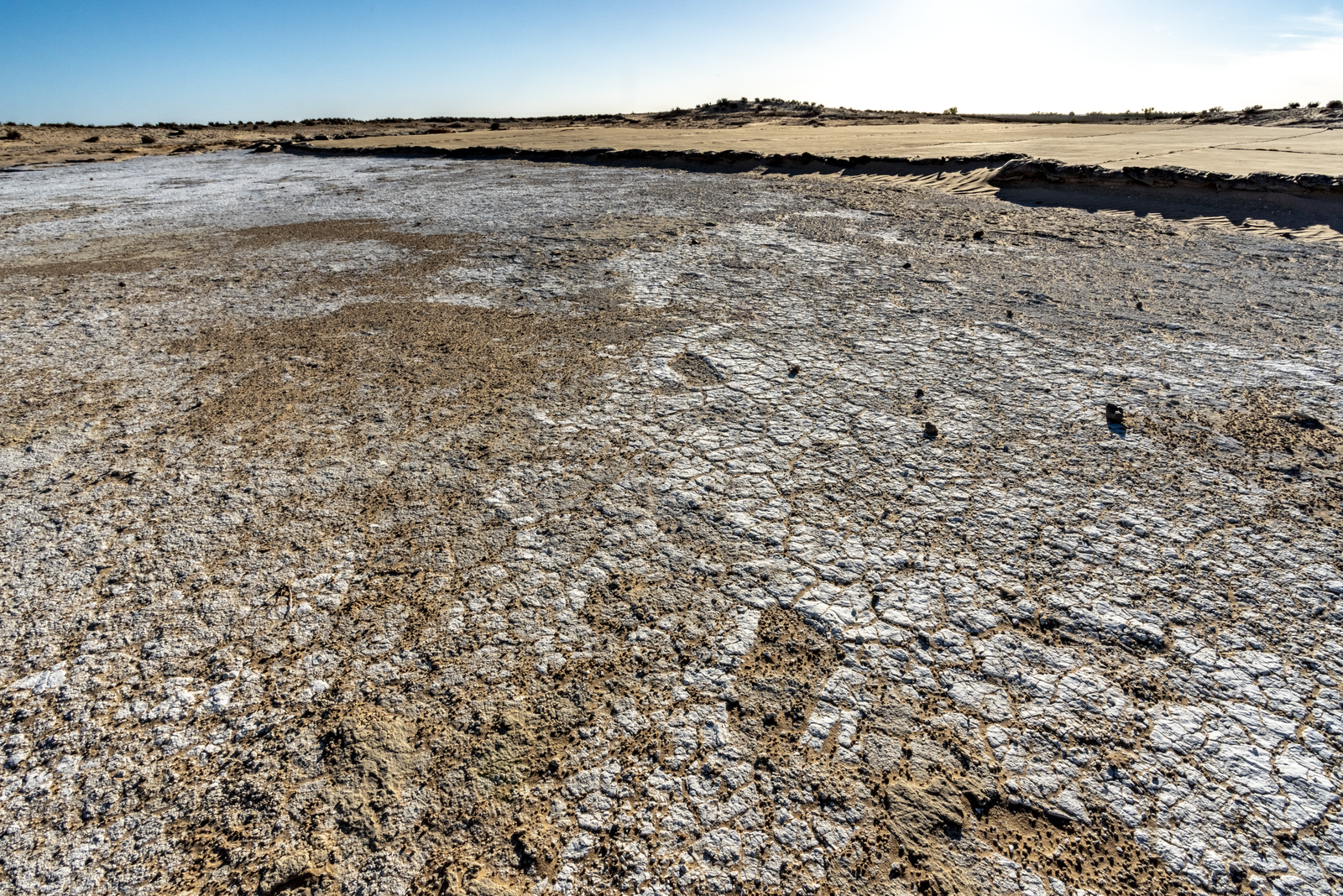

When I arrived at Borroloola in January 1980 it was in the middle of a torrential tropical downpour and I had just flown 1000 kilometres from Darwin in a light aircraft. I recall never having seen rain like this, and secondly, how red the earth was.

I learnt Yanyuwa, one of the four language spoken at Borroloola at the time, partly because many of the students I was teaching were Yanyuwa and my assistant teacher was Yanyuwa.

It was a fun process. There was no dictionary, no grammar book, just me and my pen. I still have those battered old books of learning.

I had very generous Yanyuwa teachers who would give me words and sentences that I was expected to produce in the afternoon. The hardest part of the process was making the distinction between the very distinct male and female dialects, which is a unique feature of Yanyuwa where proper speech is an expectation.

You talk about the biography of landscape and the atrocious acts of colonisation where Indigenous people, places and objects were renamed or even unnamed. Can you tell us a little more about this?

It is a great act of colonisation to remove names and silence what was once there. An easy way to understand this is to see that those taking power over land are also the ones that define what the land and those people (the original inhabitants) will become.

One has to remember that First Nations peoples in Australia were not full citizens until the 1967 referendum. In fact, up until that point, every Indigenous person, regardless of age, was defined as a ward of the state. Government officials, missionaries, cattle station owners and so forth, had control over the lives of Indigenous people, even down to what name they would be given. So male indigenous names became replaced with names like Pluto, Moses, Adolf Hitler and Mussolini; while indigenous females were given slaves names from the United States, like Dinha, Bella and Amy.

Ultimately the country was renamed and silenced.

In your large body of work preserving memories, stories and the language of the communities of Borroloola that are quickly diminishing, can you describe how you have gone about documenting and making a collection for future generations to learn from?

While I had never been asked to record knowledge, when I arrived in Borroloola I wrote anything and everything down. It was a few years later that I went back and began to formally categorise this knowledge. I began to work with family members as to how they would like to see things documented, which lead to a ongoing partnerships between myself and the families.

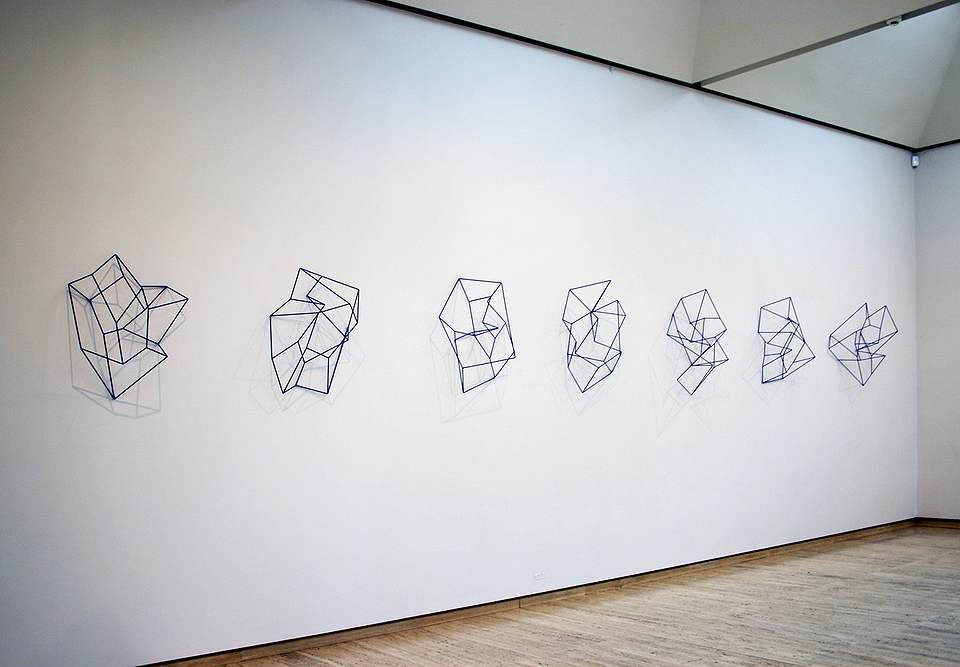

Out of this grew the dictionary and encyclopaedia of Yanyuwa, redrawing and reworking maps, joint authorship of publications, the animation project and so forth. This gave strength to what I was doing, and still does, because it becomes a relational project, and the ownership then resides with the families that own the knowledge.

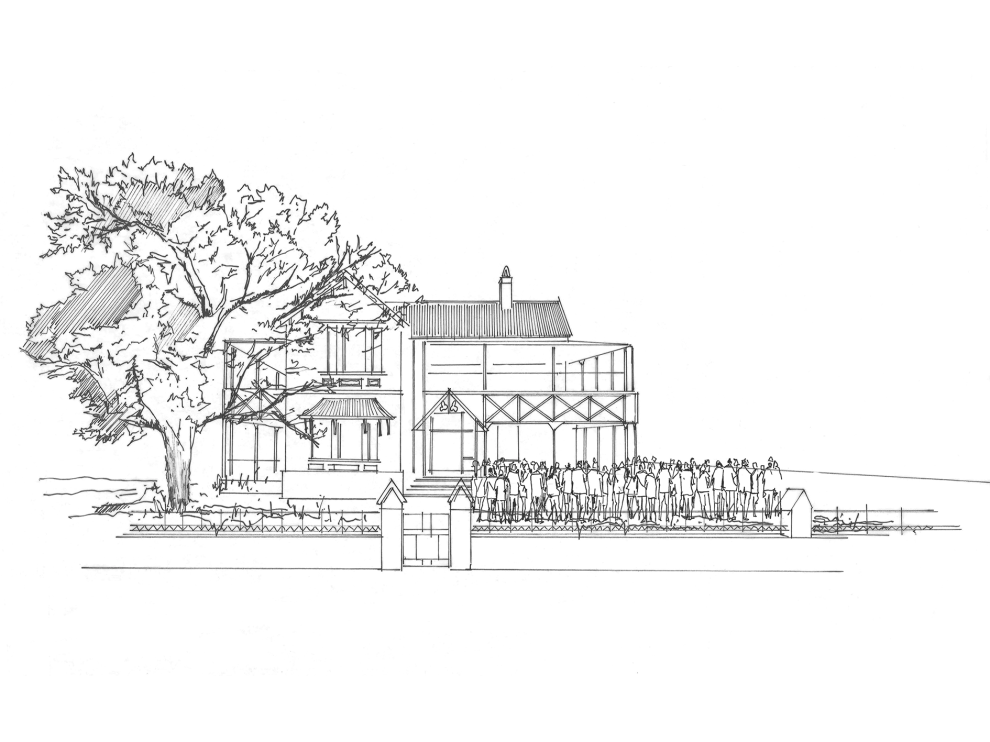

You’re currently working with Carr to create a home for this collection in Borroloola. Can you tell us more about this meeting and education space and the process you’re taking to ensure it’s sensitive to the land and its people?

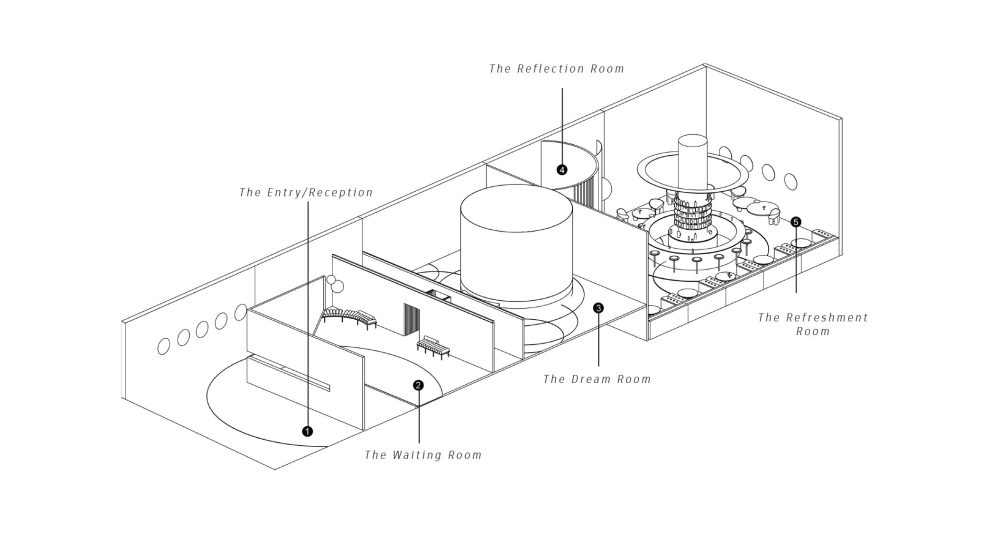

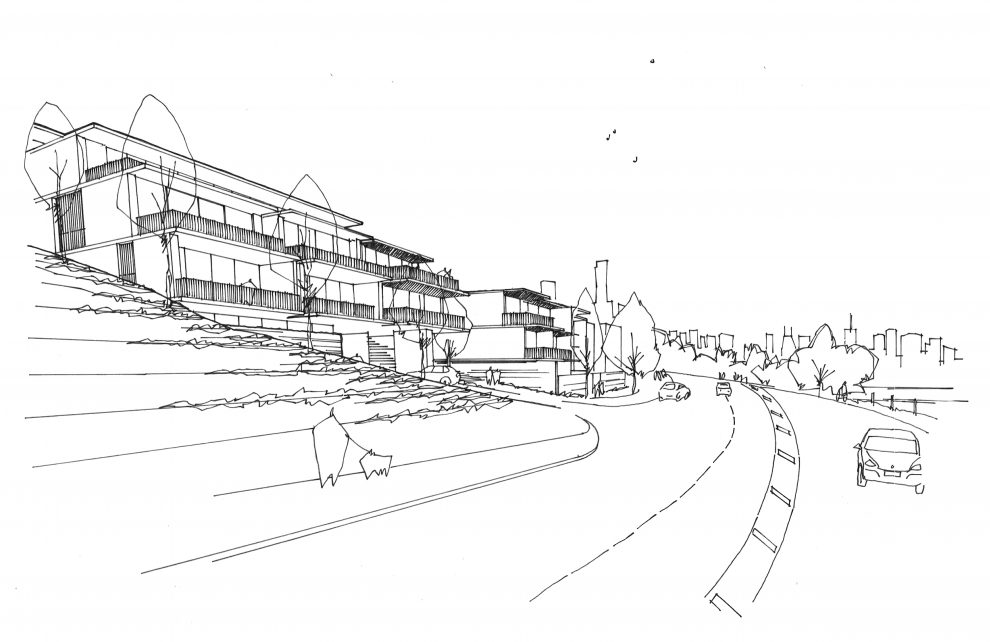

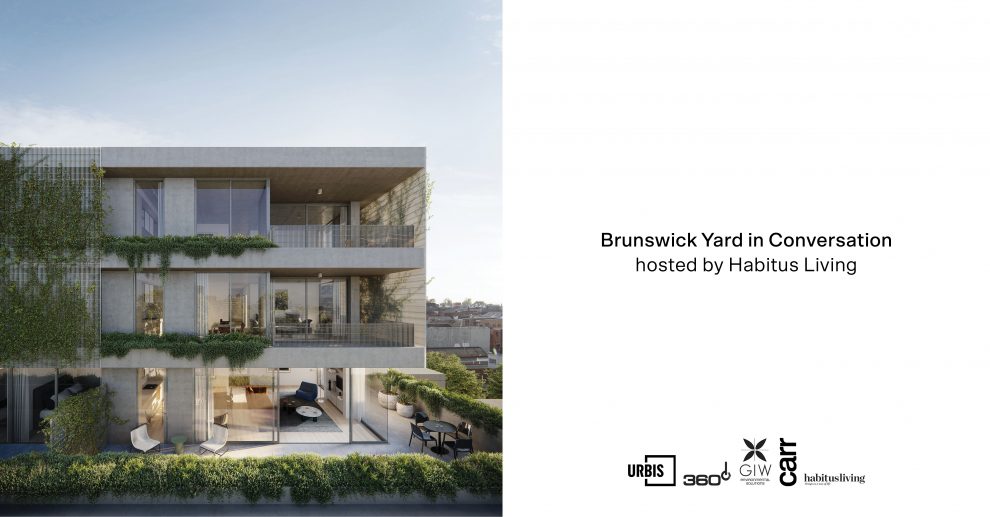

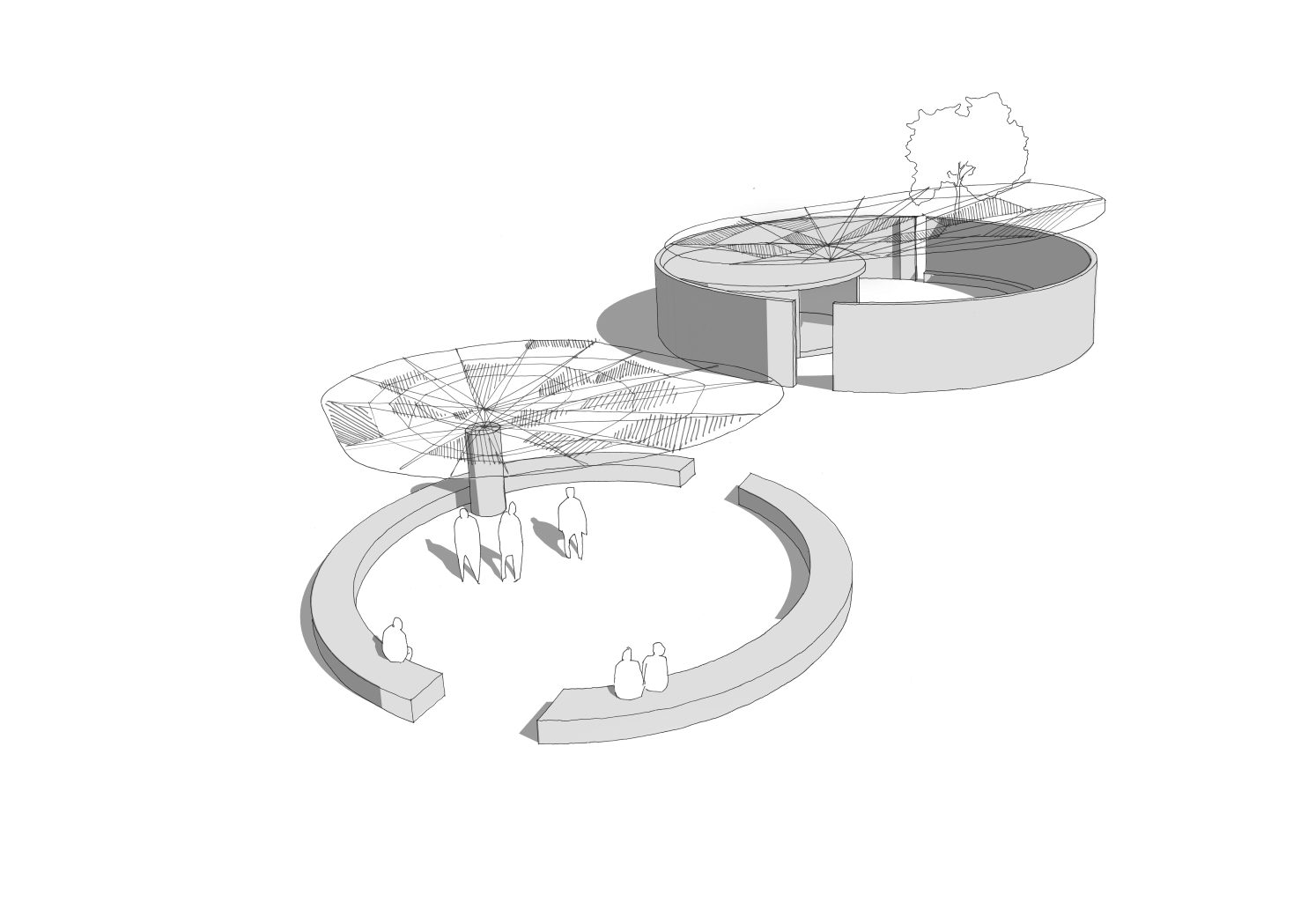

Invited to participate in this marvellous project by Tom Simpson of Simcon, Carr has designed a brilliant concept for this ‘meeting place’.

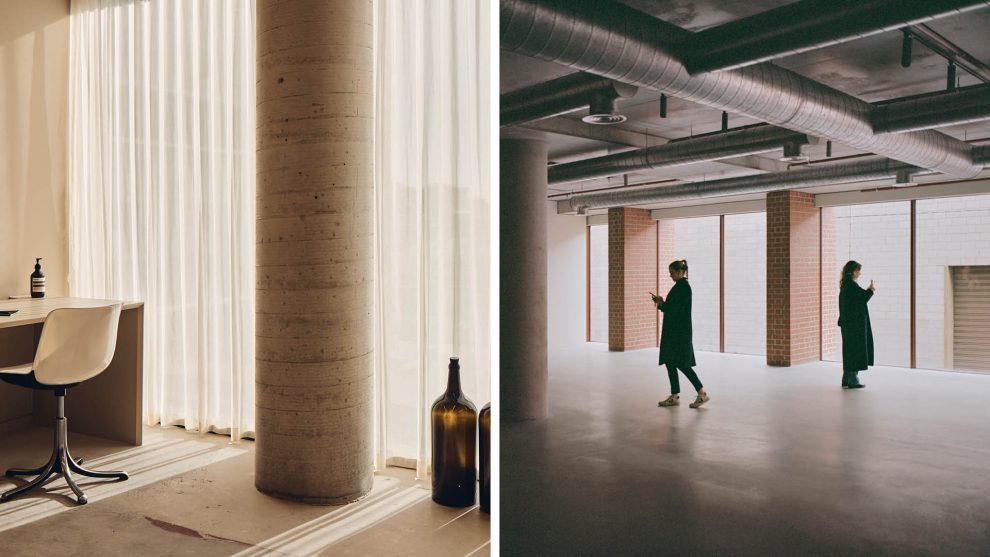

Along with teaching and learning spaces, the design comprises sensitive places to both store and display not just the objects, but also the maps and photographs of the people and history of Borroloola. The design concept includes an outside performance and meeting area that link together by pathways and sheltered areas, replacing a makeshift ‘bow shade’ that was destroyed in the cyclones of the region in early 2019.

The real beauty of this project is that the families at Borroloola have engaged with and provided feedback to the concept that will serve their communities, their language and their storytelling. Still in its infancy, the team hope to engage local employment opportunities for the people of Borroloola. Further consultation with local elders and leaders will occur as the design progresses.

Read our Q&A with Studio Ongarato and our work together on Como Terraces.