Stephen Todd, Design Editor at the Australian Financial Review, interviews Sue Carr as she reflects on her achievements and the standout projects that have defined her career.

A master at creating calm and focused interiors, the designer who eschewed curtains and cushions is celebrating 50 years in the trade.

Sue Carr is the grand dame of Australian interior design. As she celebrates 50 years in the trade – a golden jubilee – it feels timely to reflect on some of her achievements.

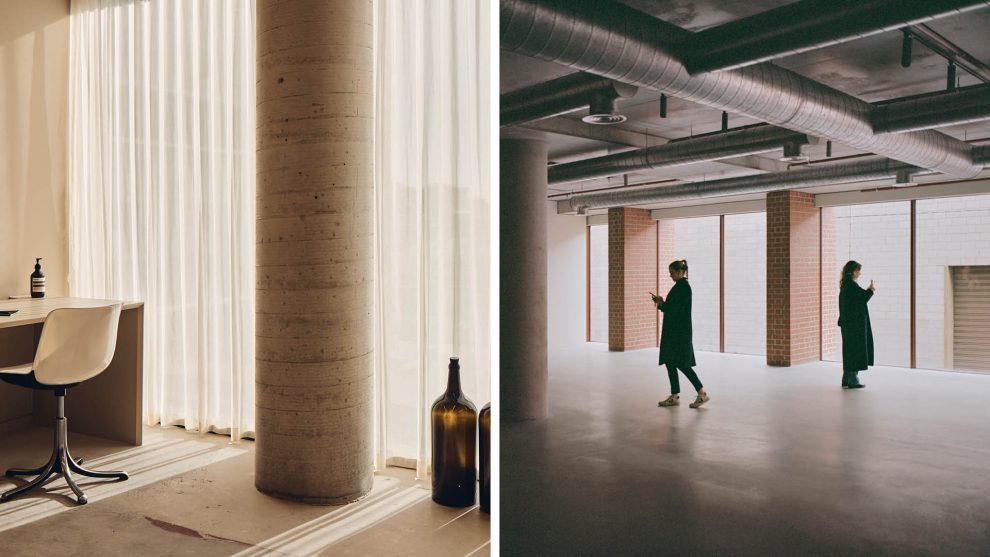

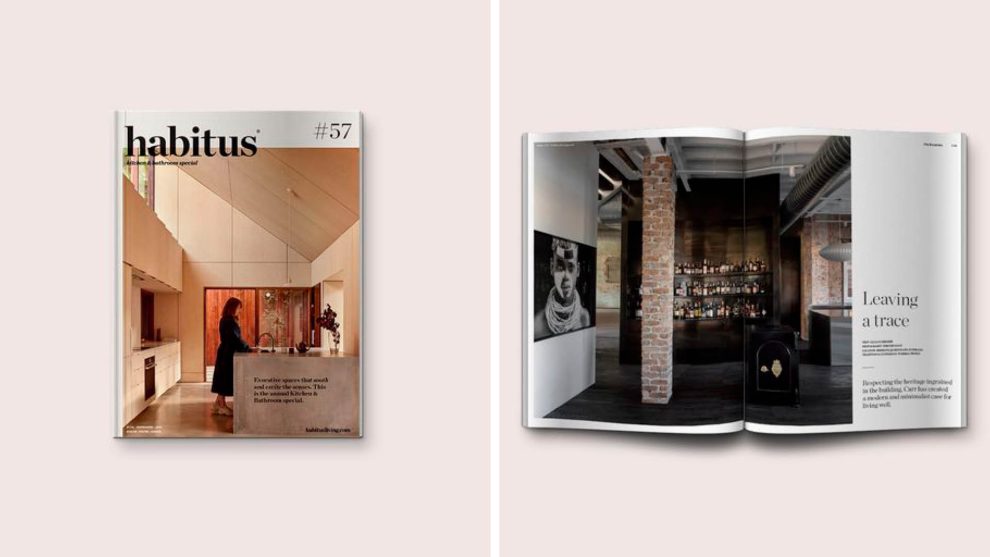

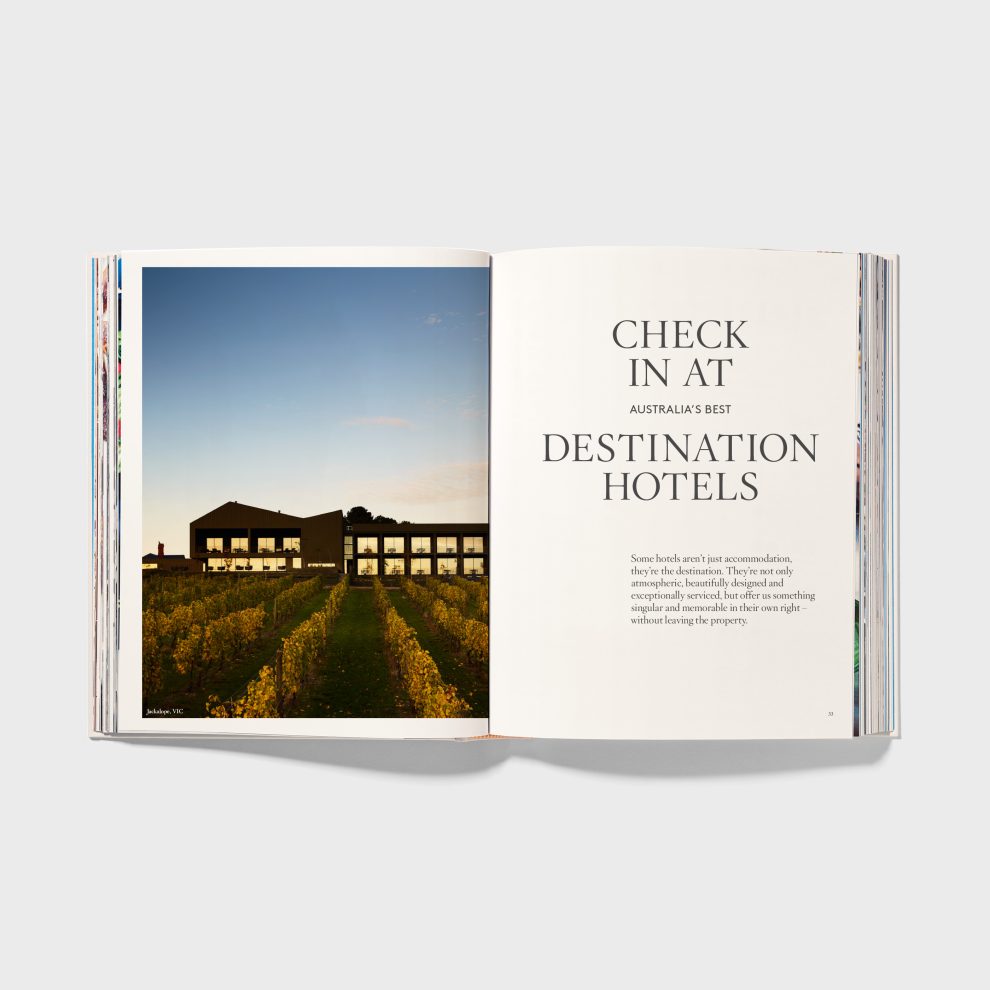

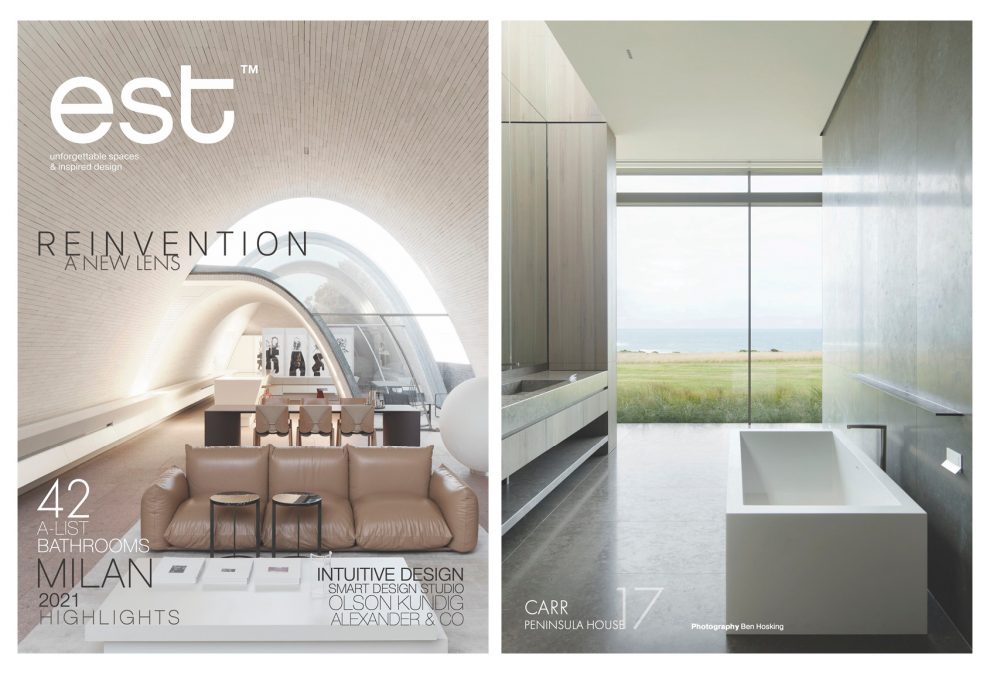

The Jackalope hotel on the Mornington Peninsula, for instance, for which Carr created moody rooms of an almost Cartesian rigour, with strict right angles rendered sensual in charred timber, offset by glimmers of brushed brass. Or the United Places hotel in South Yarra, Melbourne, where she attained maximum impact through radically reduced gestures. Essentially, it’s a sand blasted, gridded concrete façade behind which sit 12 suites featuring broad oak parquet floors and hand-trowelled walls offset by undulating folds of sumptuous velvet room dividers.

“I strive for interiors that are focused and calm, devoid of anything that might be deemed in excess,” says Carr, speaking from her home in Melbourne.

It’s a fair bet she’s uttered some version of that throughout her half-century career. A notable Carr attribute is that her vision seldom wavers.

As a young woman, she set out to be a scientist, enrolling at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT, not yet a university). But after three months contemplating her future in the flame of a Bunsen burner, she wandered past the architecture department and decided to transfer to interior design – a field so peripheral that lectures were held in a portable classroom sequestered on a rooftop.

Not that she was ever interested in “curtains and cushions”, as she puts it (in an echo of Le Corbusier’s dismissal of Charlotte Perriand when she came looking for work in 1927: “Mademoiselle, we don’t embroider cushions here”.)

“My idea of interior design was always informed by a desire to understand the structures within which the interior had to exist. For me, the inside and outside have to be in symbiosis.”

Her first job after graduation was in a small architectural practice to work on a private home in Parkville, Melbourne – “A huge challenge since I thought I knew nothing.” She then joined a large architectural firm in the CBD but found it “discouraging”, since the practice was more intent on coddling than challenging its clients.

“I realised that if I wanted interior design to advance in this country, I had to go out on my own.” – Sue Carr

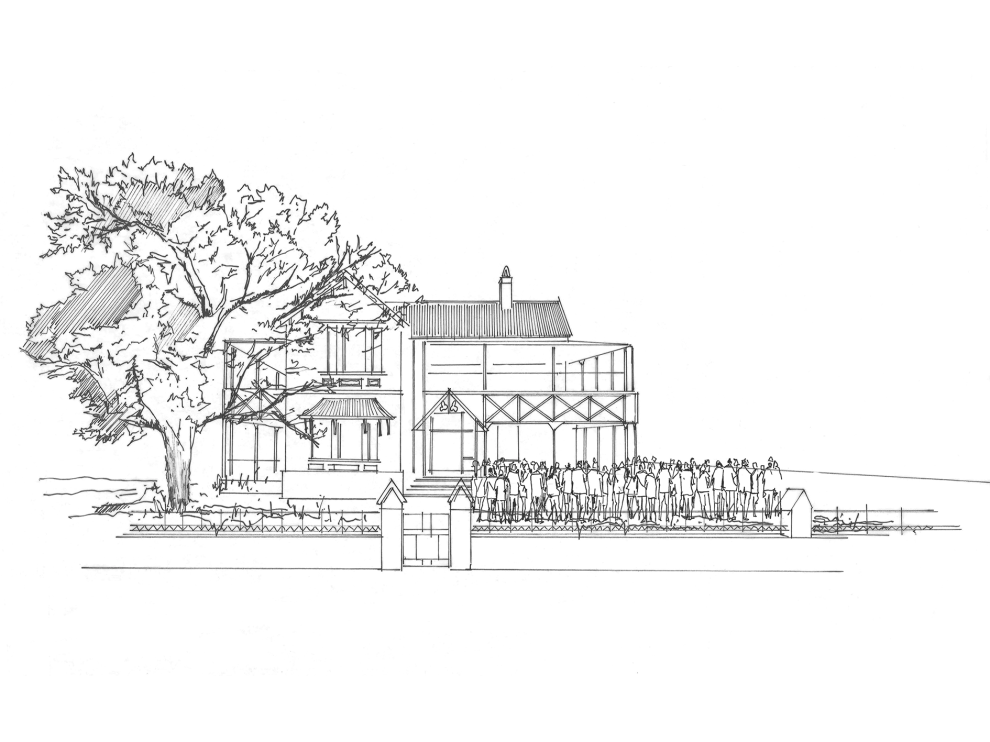

And so, in May 1971, this independent female interior designer who refused to be relegated to hanging curtains or scattering cushions, set up her own studio – initially called Inarc – in a tiny space in Murphy Street, South Yarra.

“It was just a room, really, but I thought it was fabulous,” she says. “There was no heating or cooling and for ventilation, we had to open the windows, and when we opened the windows all the documents would blow all over the place. But it was wonderful. It was the middle of recession but eventually we got work. We got our first employee about 12 months in, and work started to flow, and we were off and away.”

“From the beginning, it was my firm belief that interior design could stand alongside architecture as an equal contributor to the built form.” – Sue Carr

From the beginning, Carr embedded architects in her interior design practice – a bird-flip of sorts to all the (male-dominated) architectural practices that would occasionally deign to include a (usually female) interior designer on their team.

Launching at a time redolent of shag-pile carpets and avocado laminate,Carr’s penchant for the purity of modernist lines and minimal material flourish immediately set her apart. As the market slowly – but surely –came around to her way of thinking, Carr became the de facto prophet of a new aesthetic. Her greatest skill had been never to prevaricate even in the face of shifting trends, her approach transcending mere style to attain the force of philosophy.

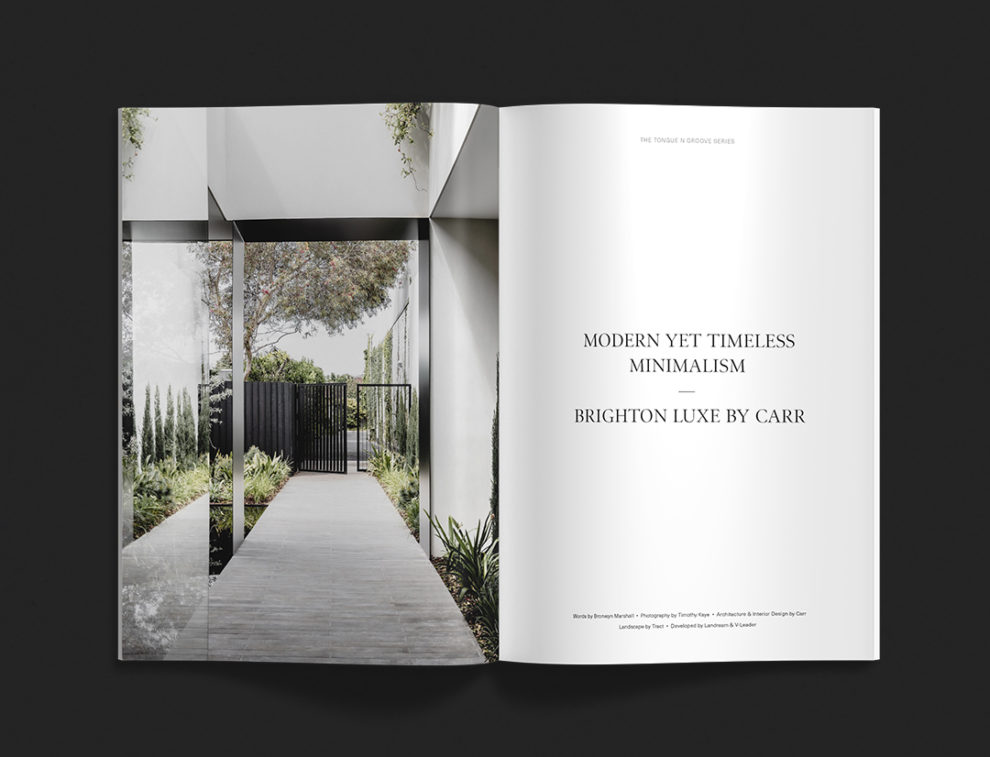

Carr refers to her approach as “dynamic restraint”. Let’s just call it timelessness. You can sense this dynamic restraint in the sprawling private residence she recently delivered on the Mornington Peninsula. (Well, “sprawling” as much as a low-lying, three-sided, concrete bunker can let itself go.)

Movement through the interior enfilade of concrete-floored rooms is experienced as a series of rhythmic compressions and reveals – not least to the melancholic bay immediately beyond its floor-to-ceiling windows.

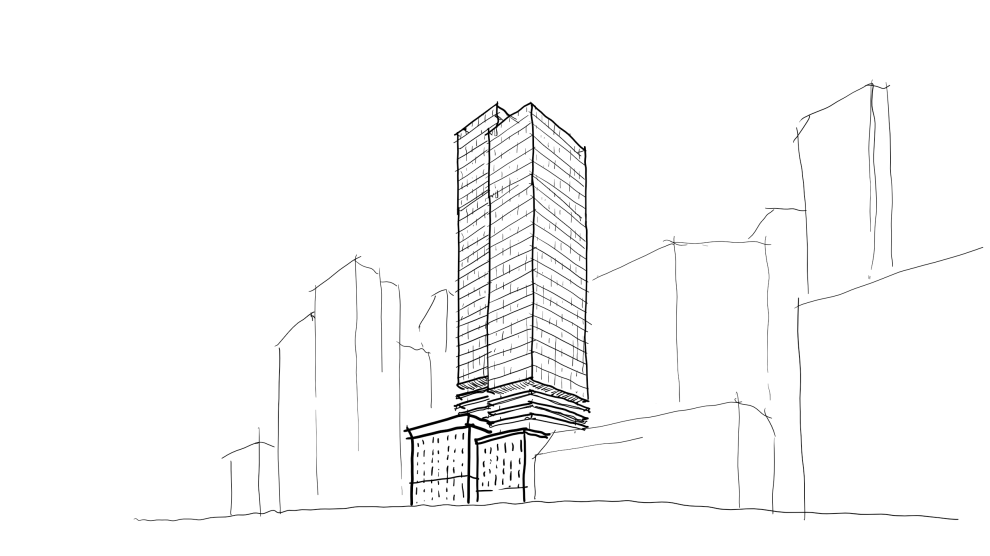

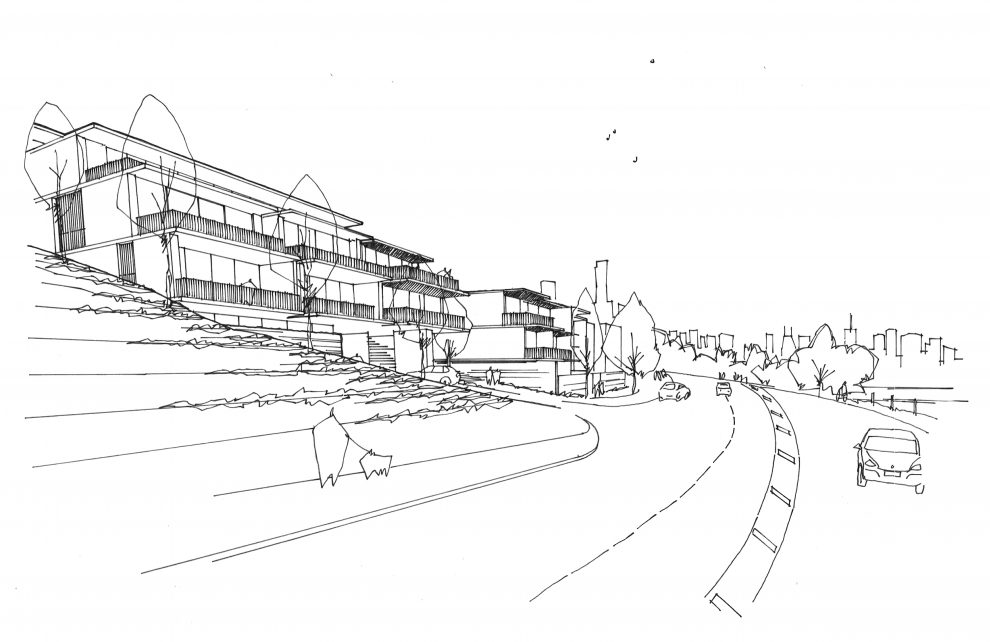

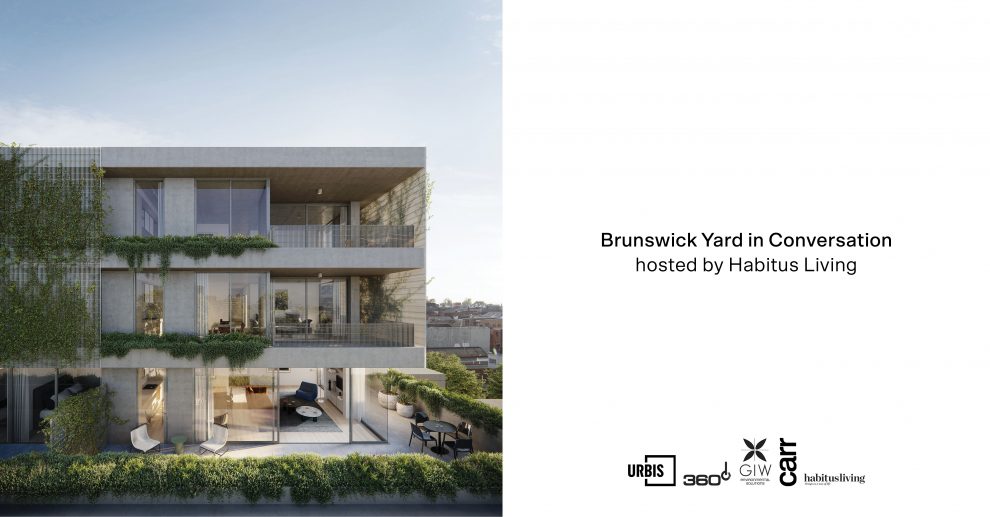

You can feel it, too, in the stacked concrete and steel I-beam construction of Carr’s Victoria & Burke apartment block in Camberwell, due to be completed next year. The rugged cantilevers add a stoic sculptural element to the streetscape while full-height sliding panels open the apartments up to the garden and out to city views.

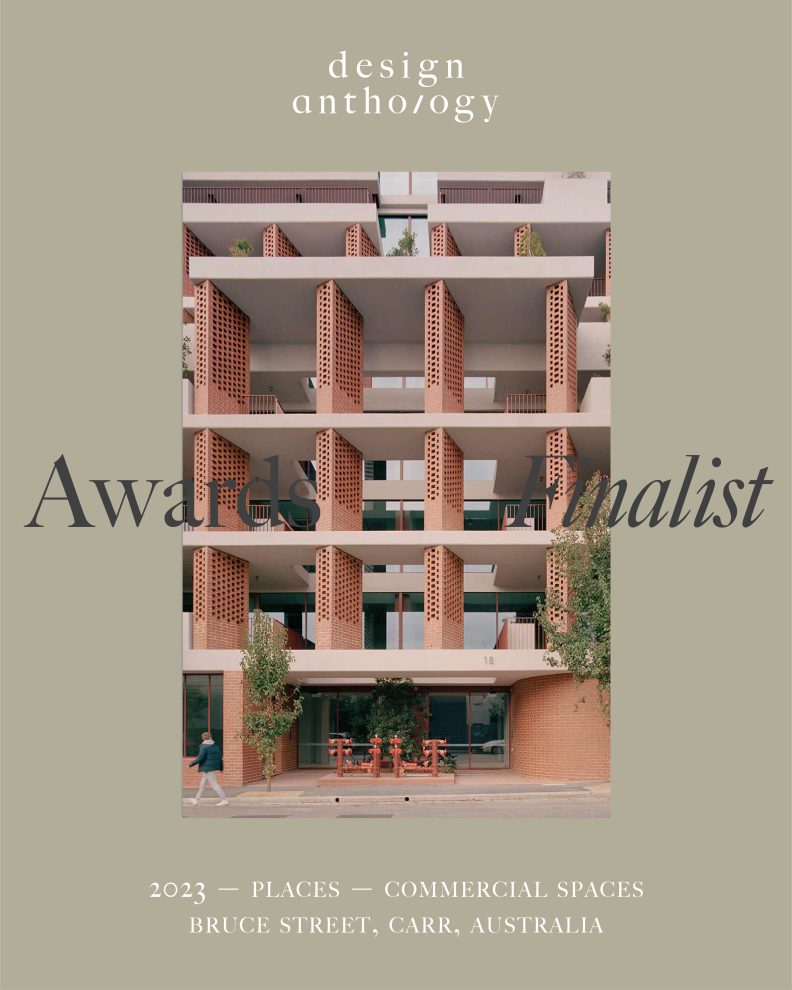

If you’ve not got access to either of those builds, you can always experience Carr’s deft articulation of the inside/outside dialogue at the Olderfleet office building on Collins Street, designed in collaboration with Grimshaw Architects.

Entered via a darkened entrance portal, the lobby area occupies a dramatic light-filled atrium between the red-brick heritage structure and the sleek new concrete and marble build. Furnishings are a mix of paradoxically slick rustic and chic mid-century leather classics; the whole lot working together to create a space not of passage but of pleasurable sojourn.

“Sue is a master at creating interiors that seamlessly meld the inside and outside of a building. At Olderfleet it’s difficult to discern where our work ends and her work begins, and that creates a delightful user experience” – Neil Stonell, managing partner of the Melbourne office of Grimshaw.

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

As published by Australian Financial Review, written by Stephen Todd. You can access the original AFR article here.